Our behavior is shaped by a combination of knowledge in the head and knowledge in the world.

Knowledge in the head is knowledge in the human memory system. Knowledge in the world is the information in the environments that help people perform tasks, including signifiers, natural mappings, and constraints. Both are essential in our daily functioning, but we can choose to lean more heavily on one or the other.

But human memory is complex. Short-term memory (STM) is easily distracted or disrupted and conscious thinking takes time and effort. Because of this, we often rely on knowledge in the world. These external cues given to us reduces the burden of recollection and guides our actions; they are not dependent on our conscious process of thinking.

IKEA, a Swedish furniture store, is full of signifiers. Signifiers are cues that indicate what actions can be performed and how to do so. They signal the affordances, which are the inherent possibilities for an action within an object.

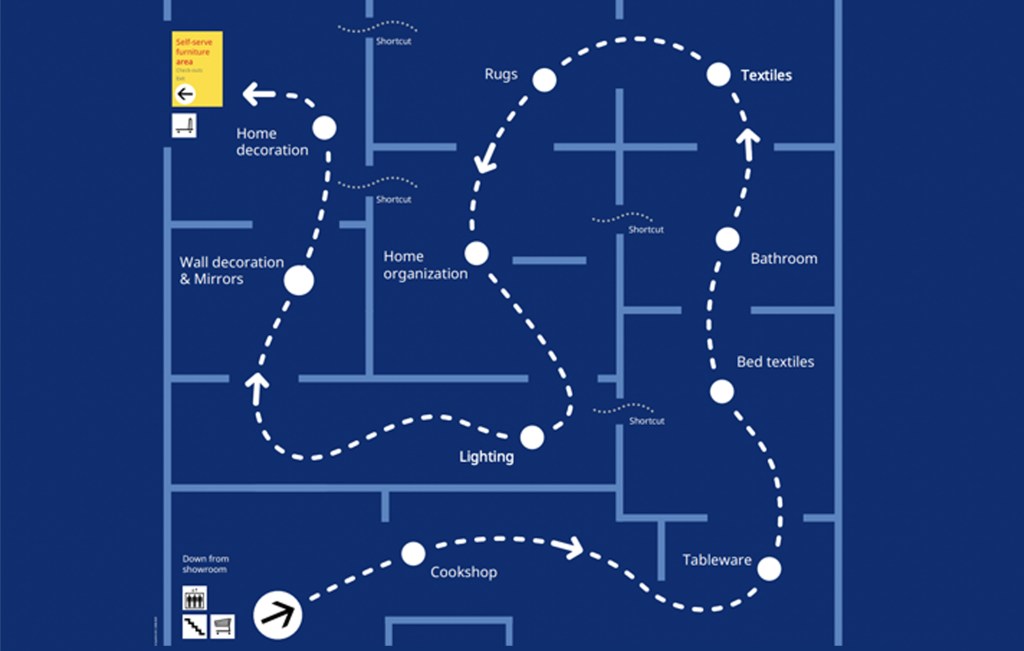

Arrows on the showroom floor signal the intended fixed walking path and guide you through the store in a one-way system that keeps shoppers focused while limiting distractions; This layout still gives customers the autonomy to stray off the path and shop in the sections, but gives them guidance through the showrooms. The maze structure itself keeps customers curious by not showing them what is next, but lays out enough direction and signage as to relieve any confusion or concern.

In addition, tags on furniture show the name, price, and warehouse location of each product, telling you where to go if wanting to purchase a product. Each entrance and exit is clearly marked with arrows, eliminating the possibilities of getting lost in the store’s warehouse layout.

Even their food court, a lesser visited gem of IKEA, has clear signage and a tray rail system, ensuring that customers are guided through each step of this food-court experience and proceed through the line correctly.

By staging furniture in realistic home settings, IKEA also lessens our mental load by providing contextual examples for how their items can be placed, allowing our brains to instantly process possible ways these pieces can fit into our own spaces.

According to Don Norman, cognitive scientist and author of The Design of Everyday Things, conscious thinking takes time and mental resources. Knowledge in the wold can be a beneficial tool for remembering and guiding when available in the right moments.

Knowledge in the head is efficient: no search and interpretation of the environment is required.

Author of The Design of Everyday Things, Don Norman.

Instead of trying to imagine how a furniture piece fits into your living room, the environment itself reminds you of how the product will look. With a self-assembly furniture company like this, having an example of the physical product built in front of you also lessens the mental load of trying to gauge measurements, colors, and other characteristics of the pieces.

IKEA utilizes Norman’s practice of ‘natural mapping;’ the showroom floor itself acts as a natural map, guiding customers along a logical path through the store. This attempt to make the layout intuitive and self-explanatory allows people to navigate the large warehouse space by following the path provided.

Side note: natural mapping can vary from culture to culture, and as a Swedish brand, IKEA’s layout is unique. Their view of utilizing explicit signage and paths is a perfectly logical way to view the world.

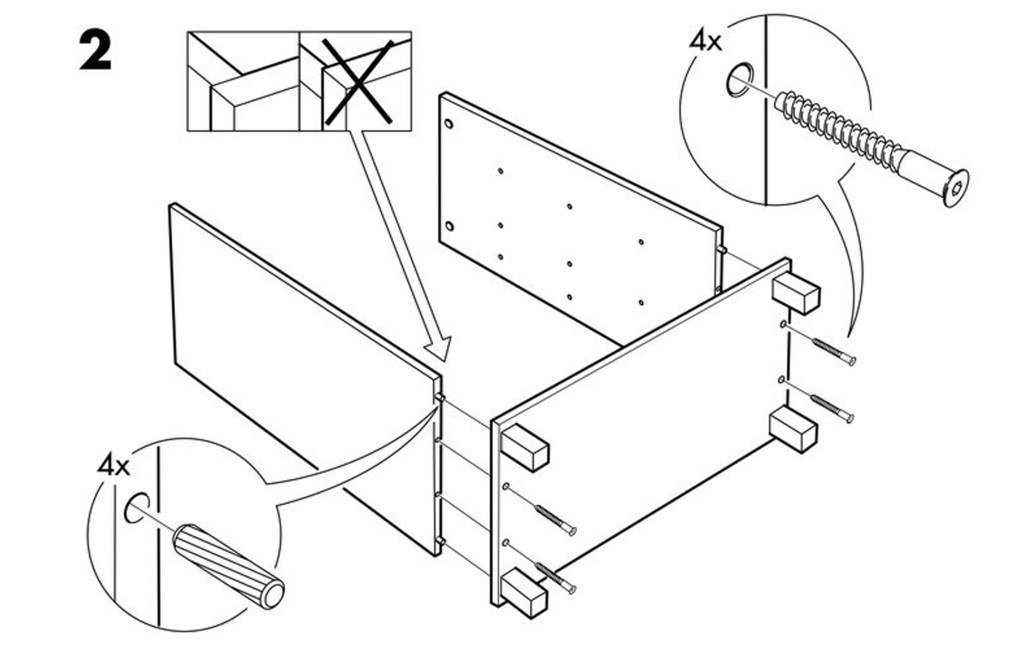

IKEA’s practices also overlap with Norman’s philosophy in its use of constraints. Although their furniture comes in a ‘flat-pack’ cardboard box with a million pieces, each of those pieces has a place.

A dresser from IKEA comes with pre-drilled holes, labeled screws, and plywood panels that only fit in specific orientations. The design of each piece ensures that users instinctively assemble the piece correctly with very little mental tax, even if they’ve never built furniture before.

These provided external constraints, such as the shape of each part or the individually labeled pieces, actively guide the customer, preventing mistakes and reducing the overall cognitive load. The instructions are also carefully structured to guide the assembly process, further lessening that need for learned knowledge.

What previously looked like a large amount of decisions and mental work is reduced to only a few choices. These external constraints exert control over the permissible choices, making this seemingly daunting almost easy for the average customer. IKEA has now even begun to create disassembly instructions for their furniture pieces, ensuring the customer is taken care of at every phase of their product ownership.

By complementing the existing knowledge in the head with the knowledge in the world provided by IKEA, customers don’t have to rely solely on their memory or problem-solving capabilities, but instead can lean on the tools provided in their environment, whether that be in the store (signage/arrows) or at home (instruction manual & labeled parts).

This balance between knowledge in the head and knowledge in the world creates a unique shopping experience at IKEA where customers feel guided with a lessened cognitive load.